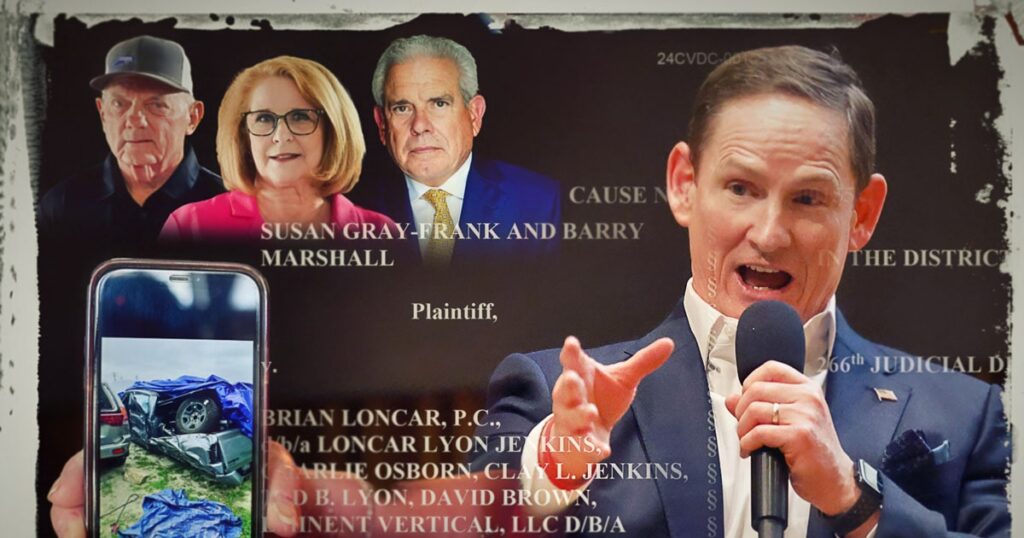

The calls began two days after a driver crashed into Barry Marshall’s Dodge Ram, totaling the truck but sparing his life.

His wife, Susan Gray-Frank, said the stranger offered to help wrangle more money from their insurance company before she hung up.

Then Marshall said his phone began ringing and stopped only when he picked up the sixth call from a spoof number.

He agreed to be transferred to a law firm, and about 20 minutes later, an email arrived asking him to sign a contract with one of the most prominent personal injury firms in Texas: Loncar Lyon Jenkins, owned by former state Sen. Ted Lyon and Dallas County Judge Clay Lewis Jenkins.

Instead of hiring the firm, the couple sued Loncar Lyon Jenkins for illegal solicitation, or barratry, alleging case runners contacted them out of the blue to drum up business for the attorneys.

Ambulance chasing is rampant in Texas but can be difficult to prove with degrees of separation between lawyers and intermediaries used to engage with crash victims.

While it’s illegal for attorneys or their proxies to initiate contact with potential clients within 30 days of an accident, state disciplinary rules allow lawyers to pay online services to refer clients seeking help. With no direct oversight by the state bar, tactics of lead generators can become tangled in allegations of barratry.

Loncar Lyon Jenkins denies the firm solicited the couple but how the calls originated is unclear in the ongoing case filed in Erath County in June.

During a March 4 hearing, Ryan Taylor, an attorney for Loncar Lyon Jenkins, confirmed their lead generation service transferred Marshall to the law firm. But Taylor denied they are affiliated with the “mysterious entity” that initially called the couple before passing Marshall to the lead generator.

He said nobody associated with the law firm called Gray-Frank or Marshall.

“But somebody did,” responded Erath County District Court Judge Jason Cashon.

Loncar Lyon Jenkins declined to answer specific questions about the case or make Jenkins, Lyon or COO David Brown, who are named as defendants, available for comment. In court filings, the firm called the lawsuit “an extortive money grab” by the couple’s attorney, Tom Carse.

They’ve countersued the couple for filing “a frivolous suit” and asked the judge to disqualify Carse for a litany of claims, like allegedly offering to pay an informant to testify against the firm.

Carse has built a niche suing other lawyers for barratry in Texas but denies allegations of wrongdoing.

“If you broke the rules, shame on me for enforcing a civil penalty on behalf of a client you hustled,” Carse said.

‘It is rampant’

Barratry has long been a crime in Texas, applying not only to lawyers but also to chiropractors, physicians and private investigators. The idea is that people in need should find help through a trusted source or their own research, not by providers trying to instigate business.

Attorneys were barred from advertising until 1976, when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled it was a First Amendment right.

In the hours and days after car accidents, victims still get bombarded with calls from case runners working for law firms trying to profit by hoarding cases in bulk, legal experts say.

With few criminal prosecutions cracking down on barratry, the Legislature in 2011 enacted a civil statute that allows victims who were solicited to receive damages even if they never ended up signing a contract with the law firm.

The problem still remains pervasive and can cause people in crises to hire attorneys who are harvesting cases for quick payouts instead of fighting for the best outcome, said Todd Clement, president-elect of the Texas Trial Lawyers Association.

To push back, the association backed a bill this legislative session to increase the civil penalty on offending attorneys and their agents from $10,000 to $50,000.

“It’s a bigger problem now than it’s ever been. It is rampant,” Clement said.

Case runners often find accident victims by pulling crash reports filed with the Texas Department of Transportation – a modern update to leaning on tow truck drivers, funeral homes and first responders for leads.

They typically call pretending to be with a nonprofit or a vague-sounding state agency “to bait the client” into talking with an attorney, said Houston legal malpractice attorney David Kassab, who files barratry lawsuits on behalf of victims.

“It puts pressure on the potential client to make a decision and it takes away from their opportunity to investigate lawyers out there that may be better or more qualified,” Kassab said.

At the same time, online services that intake information from clients who are looking for legal help and refer them to law firms have existed for decades with little regulation.

The last time the state ethics commission issued an opinion with guidance on the industry was 2006, a lifetime ago in social media.

The disciplinary rules still don’t mention “lead generation,” but the state bar published a three-sentence commentary on the topic in 2021.

It clarified that attorneys can pay for leads but not based on the outcome of those cases and that intermediaries have to refer attorneys from a rotation, and not recommend one over another.

Online lead generation tactics have since evolved from basic digital directories clients use to browse for law firms.

These days, someone can search online about what to do after a car crash — then watch their social media feeds flood with targeted advertisements from lead generators. Many posts make no mention of hiring an attorney but offer “free crash reports” or a tool to calculate what their injuries could be worth.

Once a user is successfully baited, enters a phone number and agrees to be contacted, the calls begin from lead generators asking if they want to be transferred to an attorney — the underlying motivation behind the flurry of unrelated ads, said Jim Zadeh, an adjunct law professor at Texas A&M University’s law school.

The state bar regulates lawyers — not the private businesses they hire — so it’s up to the attorney to ensure lead generators get consent before contacting potential clients, said Gene Major, director of the Texas bar’s attorney compliance division.

Some tactics to get consent for contact can be so misleading, a lay person may not be able to differentiate them from solicitation, said Jeanne Huey, a Dallas trial lawyer and legal ethics expert. If an attorney can’t confirm how their lead generator got a client’s information, she said it can lead to damaging allegations of barratry even if the encounter was permissible under vague rules.

“You are trusting your practice, your reputation, perhaps, with a third party who you have no control over, no ability to regulate,” Huey said.

Motives questioned

Carse said he began suing other lawyers for barratry a decade ago when he saw almost no criminal prosecutions cracking down on the problem.

Prosecutors and law enforcement have long viewed it as a victimless crime, or as a civil matter, and prioritize violent offenses, said Guy Choate, a San Angelo personal injury attorney.

Policing the offense largely falls to civil court, but some of Carse’s targets allege a less noble motivation.

Although he has sued countless others for barratry, Carse has also defended one marketing firm against those same allegations – because, he said, they acquired leads legally.

In an April 9 motion, Ronald Wright, an attorney representing Loncar Lyon Jenkins, sought to disqualify Carse from the case in Erath County, citing a Dallas woman who alleged Carse used her to get information on law firms and lead generators competing with him.

Ana Hernandez hired Carse last year to sue a lead generation company in Collin County for firing her after she accused it of being a barratry scheme culling crash victims’ information.

Their relationship devolved, and court records show Carse withdrew as her attorney on Oct. 29. The next day, Hernandez met with Wright to share concerns about Carse, according to Wright’s motion to disqualify.

During their meeting, Hernandez wrote an affidavit alleging Carse offered her compensation to testify against Loncar Lyon Jenkins after she provided him information about the law firm.

“There is no truth whatsoever to that,” Carse said.

Among other allegations, Hernandez stated Carse added a defendant to her Collin County wrongful termination complaint after she told him she never worked with that woman.

In February, the judge in the case sanctioned Carse to five hours of ethics training for including allegations against the woman “which he knew were false,” according to the order. Carse appealed, which is ongoing, saying the defendant used an alias Hernandez didn’t recognize. Hernandez did not respond to requests for comment.

In his motion to disqualify Carse from the Erath County complaint, Wright cited Carse’s “history of unethical behavior in the procurement and prosecution of his barratry lawsuits.” A hearing on the request is set for May 29. Carse called the allegations a distraction.

“When the case is not going well for the defendant, it’s not uncommon to shift, to pivot and beat on the lawyer representing the plaintiff,” Carse said.

The ‘mysterious entity’

Susan Gray-Frank was not in the accident that destroyed her husband’s truck, but Carse alleges she got the first call from a case runner because her name was on the title.

She said the man on the phone suggested he was with a group called www.liftyouup.org. Court records show the caller texted her a link to the website, which lists hundreds of attorneys, mental health resources and other aid services with no disclosure of who created it.

On that same morning, Marshall picked up one of several calls from a spoof number. Five minutes into that call, he received an email that included his Texas Department of Transportation crash report.

Court records show the email came from a lead generation company owned by Robert Paschall, who does digital marketing for Loncar Lyon Jenkins and is also a named defendant in the lawsuit.

To obtain the report, the lead generator falsely stated on a state website they were an “authorized representative” of Marshall, according to the complaint.

Paschall stated in a deposition that www.liftyouup.org transferred Marshall’s call to his company, but both Paschall and Loncar Lyon Jenkins said they have no affiliation with the website.

When asked during the deposition why a group to which he had no connection would send his company a free lead, Paschall said, “I have no idea.”

During a March 4 hearing, Ryan Taylor, an attorney representing Loncar Lyon Jenkins, alleged the couple received calls from www.liftyouup.org because they clicked on an ad requesting one.

“You’ve got to tie liftyouup.org with Loncar, and he cannot do that,” Taylor said. “There is not a piece of evidence to do it, not one.”

Carse countered that the firm had submitted no evidence the couple clicked on an ad.

He told the judge it didn’t matter whether the firm itself initiated contact because the barratry law prohibits an agent from doing it on its behalf.

“I don’t have to have evidence that any partner at the Loncar firm called, texted, emailed, sent a letter or knocked on the front door of Susan Gray-Frank’s home because I’ve got evidence of the other person doing it, the agent,” Carse said.

Loncar Lyon Jenkins submitted a transcript of the end of the call between Marshall and the firm’s lead generator, but it did not reflect dialogue from the beginning of the call.

According to the transcript, the lead generator transferred Marshall to the law firm but first asked him three questions: Was it true the law firm did not contact him and that she was making the referral? Was it true he was hurt? And did he want to be transferred to Loncar Lyon Jenkins to handle his case?

He answered yes to all three.

A representative of Loncar Lyon Jenkins then emailed Marshall a contract, records show.

The couple didn’t sign it.

Gray-Frank said it didn’t feel right, and a colleague at work later referred her to a lawyer he trusted at another high-profile firm.

Attorney Mark Frenkel confirmed that once his firm took on their personal injury case, it referred the couple to Carse to file a potential barratry claim.

During the March 4 hearing, Loncar Lyon Jenkins asked the judge to rule there was not enough evidence for the case to continue. He denied their motion.

A trial date has not been set.