In an effort to preserve city history, Fort Worth Report agreed to archive more than 40 of Weiner’s local history columns beginning in 2025. This column originally ran in the Fort Worth Star-Telegram June 11, 2022, and was updated in 2025 for the Report.

Countdown to the Cliburn

The 17th Van Cliburn International Piano Competition kicks off in Fort Worth May 21 to June 7. The Fort Worth Report will provide in-depth coverage of the competition. Follow the score here.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 led to canceled performances in the West for scores of performers with ties to the Kremlin. But at the Van Cliburn competition in Fort Worth, officials refused to play politics. They did not alter the lineup at the 16th Van Cliburn International Piano Competition.

Now, military hostilities will not impact the 17th edition of the 18-day musical marathon that begins May 21. Although U.S. sanctions against Russia continue, there is no longer talk of cultural boycotts. Among the 30 pianists competing in this year’s Cliburn, five are from Russia, five from the United States and one represents Ukraine.

Music should remain above politics, Cliburn officials contend.

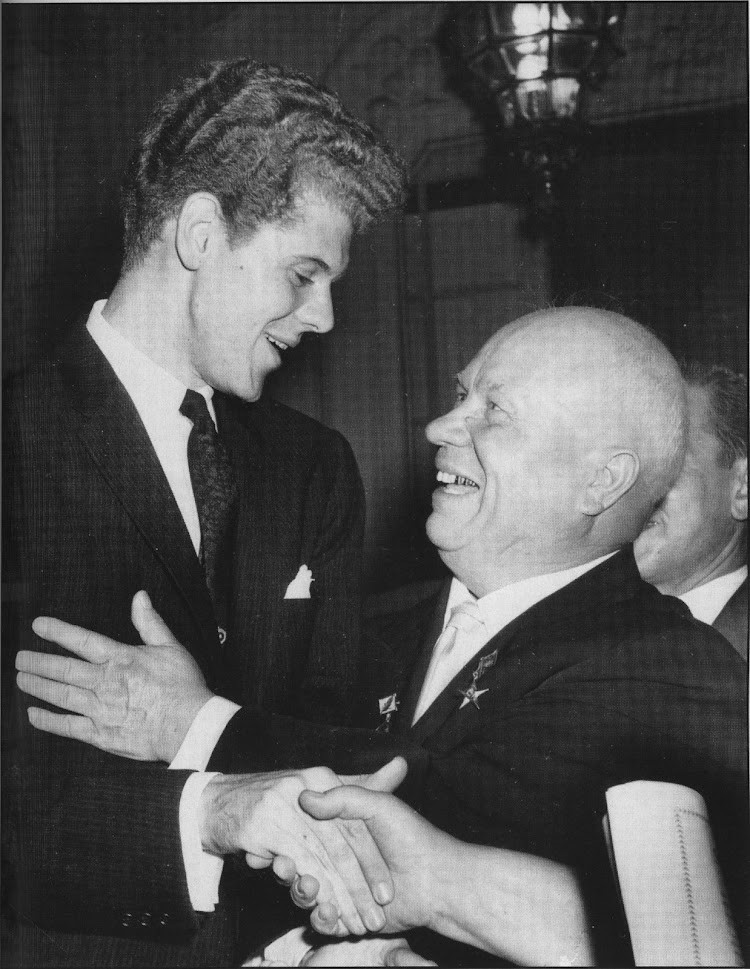

Yet, politics is interwoven in the Cliburn Competition’s history. Contest namesake Van Cliburn rocketed to fame during the Cold War when the 23-year-old pianist won first prize at the inaugural International Tchaikovsky Competition in October 1958 — six months after Russia shocked the world and punctured America’s prestige with the launch of Sputnik. As Cliburn played Rachmaninoff in Moscow, audiences swooned and threw rose petals on stage. New York welcomed the victor home with a ticker-tape parade. He later declared himself “a musical grandchild of Russia.”

The Texan’s fame temporarily thawed the chill in U.S.-Soviet relations. It sparked the start of Fort Worth’s piano competition four years later. At the first piano festival, Russian-born Nikolai Petrov won the silver medal. Another Russian, Mikhail Voskresensky, took home the bronze — then in 2022 immigrated to the United States to protest the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

At the fourth Cliburn in 1973, another Russian, Vladimir Viardo, won the grand prize. He was the houseguest of competition president Martha Hyder, whose whirlwind personality propelled the competition to great heights. She personally escorted the 23-year-old on his American concert tour. When a Cleveland snowstorm canceled their commercial flight to Cincinnati, she whipped out her American Express card and chartered a four-seat prop plane to reach his engagement. Such lessons in capitalism were interrupted within a year when the Soviet Union revoked Viardo’s travel visa without explanation.

At the next Cliburn in 1977, South African Steven De Groote won the gold, but all the buzz was about the Russians — always a force in classical music. Silver medalist Alexander “Lexo” Toradze had such an explosive, percussive style that he broke two keys on the Steinway grand at his host family’s home. The piano hammers split, leading to jokes that he held a black belt in piano. While touring in Spain in 1983, Lexo, a Georgian native, evaded his Soviet handlers and requested asylum at the American embassy. In 1991, he became a professor at the University of Indiana and was the subject of “Kicking the Notes,” a public TV documentary.

The 1977 Cliburn shone the spotlight on another Russian, Youri Egorov, 19, who had defected to the Netherlands the year before. When Egorov did not advance to the finals, outraged Fort Worth fans raised $10,000 to match the prize awarded the winner and arranged his New York debut at Lincoln Center’s Alice Tully Hall. At the time of Egorov’s 1988 death from AIDS, he had recorded 14 classical albums.

The 1977 Cliburn Competition hosted five Soviet pianists. During the next decade, the Cold War hardened into a deep freeze. President Jimmy Carter imposed an American grain embargo against the Soviet Union. The U.S. boycotted the 1980 Moscow Olympics. The Soviets retaliated with an Eastern bloc boycott of the Los Angeles games. In 1983, President Ronald Reagan vilified Moscow as the capital of the “evil empire.” Is it any wonder that no Soviet pianists participated in the Cliburn competitions of 1981 and 1985?

Change was in the air. Emerging Soviet politician Mikhail Gorbachev began pushing for Russian reform under the concept of “glasnost,” meaning openness and transparency. The travel visa of Vladimir Viardo, revoked in late 1973, was reissued in 1987. Very much in demand, Viardo performed outside the Iron Curtain and in 1989 accepted an endowed chair at the University of North Texas, where he remains on the faculty.

At the 1989 Cliburn Competition, the winner was Alexei Sultanov, 19, an Uzbekistan native with so much personality he made guest appearances on Johnny Carson and David Letterman’s late-night shows. Tragically, Sultanov, who immigrated to Fort Worth, suffered a stroke and died in 2005.

Glasnost led to “Soviet Space,” a ground-breaking exhibit in 1991 sponsored by the Fort Worth Museum of Science and History. Eighty tons of Russian space equipment went on display. More than 200 local volunteers served as translators and docents. A cosmonaut threw the first pitch at a Texas Rangers ball game. Soviets sat in box seats with George W. Bush, then a managing partner of the team.

Two days before the exhibit opened, the museum hosted a lavish gala. Van Cliburn had such a grand time chatting in Russian with 20 Soviet VIPs that he spontaneously invited anyone within earshot to a dinner party at his home the next night. By the time guests reached Van’s mansion in Old Westover on June 28, 1991, caterers from the Fort Worth Club had set the dining room table with silver trays piled high with pasta, seafood, caviar (flown in from five states) and shots of iced Russian vodka.

Happy to be hosting his new Russian friends, Van sat down at his Steinway grand and played “Moscow Nights,” a lively Russian tune, followed by the Soviet national anthem and “The Star-Spangled Banner.” That evening, there was harmony between music and science as the Cliburn Competition again proved to be a vehicle reflecting the ups and downs in East-West relations.

Edit note: Hollace Weiner covered the 1977 Cliburn Competition for The Washington Post, the 1989 and 1993 competitions for the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, and volunteered with Cliburn’s hospitality committee during the 2013 competition.

Related

Fort Worth Report is certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative for adhering to standards for ethical journalism.

Republish This Story

![]()